Introduction

In democratic governance, the constitution of a nation is not just a legal document; it is a symbol of its political philosophy and aspirations. This intricate relationship echoes back to the ancient insights of Aristotle, whose "Politics" marked a seminal moment in the empirical analysis of governance structures. Today, as Ukraine endeavors to cement its democratic identity, setting itself apart from autocratic neighbors like Russia, its constitution emerges as a pivotal yet often overlooked element in this transformative journey.

Aristotle's contribution to political thought was profound and lasting. In his analysis of 158 city-states, Aristotle delineated three ideal forms of government—monarchy, aristocracy, and polity—and their respective corrupt versions: tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. His emphasis on empirical evidence over theoretical abstraction marked a significant deviation from his predecessors and laid a foundation for modern political science.

Fast-forwarding to the modern era, the Enlightenment and its aftermath dramatically reshaped governance. Nations began codifying laws and rights in written constitutions, reflecting Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and justice. This period saw the emergence of constitutional democracies, where the rule of law and individual rights became paramount.

Ukraine's Constitutional Crossroads

In Ukraine, a nation grappling with its identity and place in the global order, the constitution should be central to discussions about its democratic path. However, this foundational document often takes a backseat. The question that emerges is whether Ukraine's constitution mirrors its democratic aspirations or if it's mired in relics of past governance systems.

Historic Background

Ukraine's constitutional journey has been a dynamic and sometimes tumultuous one, marked by the nation's struggle for identity and sovereignty. The country's first constitution, adopted in 1996, was a significant milestone, laying the foundation for a democratic and independent Ukraine post-Soviet Union. This document was the culmination of Ukraine's desire to establish a legal framework that reflected its newfound independence and democratic aspirations.

The constitution established a semi-presidential system, balancing power between the President and the Parliament. It was a document that sought to break away from Soviet legacies, embedding principles of democracy, rule of law, and human rights. However, the journey since then has been anything but smooth. The constitution has undergone several amendments, the most notable in 2004 and 2010, reflecting the ongoing political struggles and the tug-of-war between different branches of government.

The 2004 amendments, enacted in the wake of the Orange Revolution, were aimed at strengthening parliamentary democracy by curbing presidential powers. However, these changes were short-lived, as the 2010 amendments restored many of the President's powers, a move criticized for reversing democratic gains.

In 2019, a significant amendment was made, reaffirming Ukraine's commitment to becoming a member of the European Union and NATO, reflecting its westward orientation and a clear pivot away from Russia's influence.

In stark contrast to democratic constitutional evolution stands Russia's constitutional trajectory. Since the adoption of its constitution in 1993, Russia has seen a consolidation of power in the presidency, particularly under Vladimir Putin. Amendments in 2020 further entrenched presidential authority, removed term limits, and underscored the primacy of Russian law over international norms, signaling a departure from democratic principles and a move towards authoritarianism.

A similar tendency can be observed in China. Its constitution, adopted in 1982, has been amended several times, with recent changes in 2018 eliminating presidential term limits and reinforcing the central role of the Communist Party in governing China. In a nutshell, China’s amendments reflect a strengthening of single-party rule and a further consolidation of power.

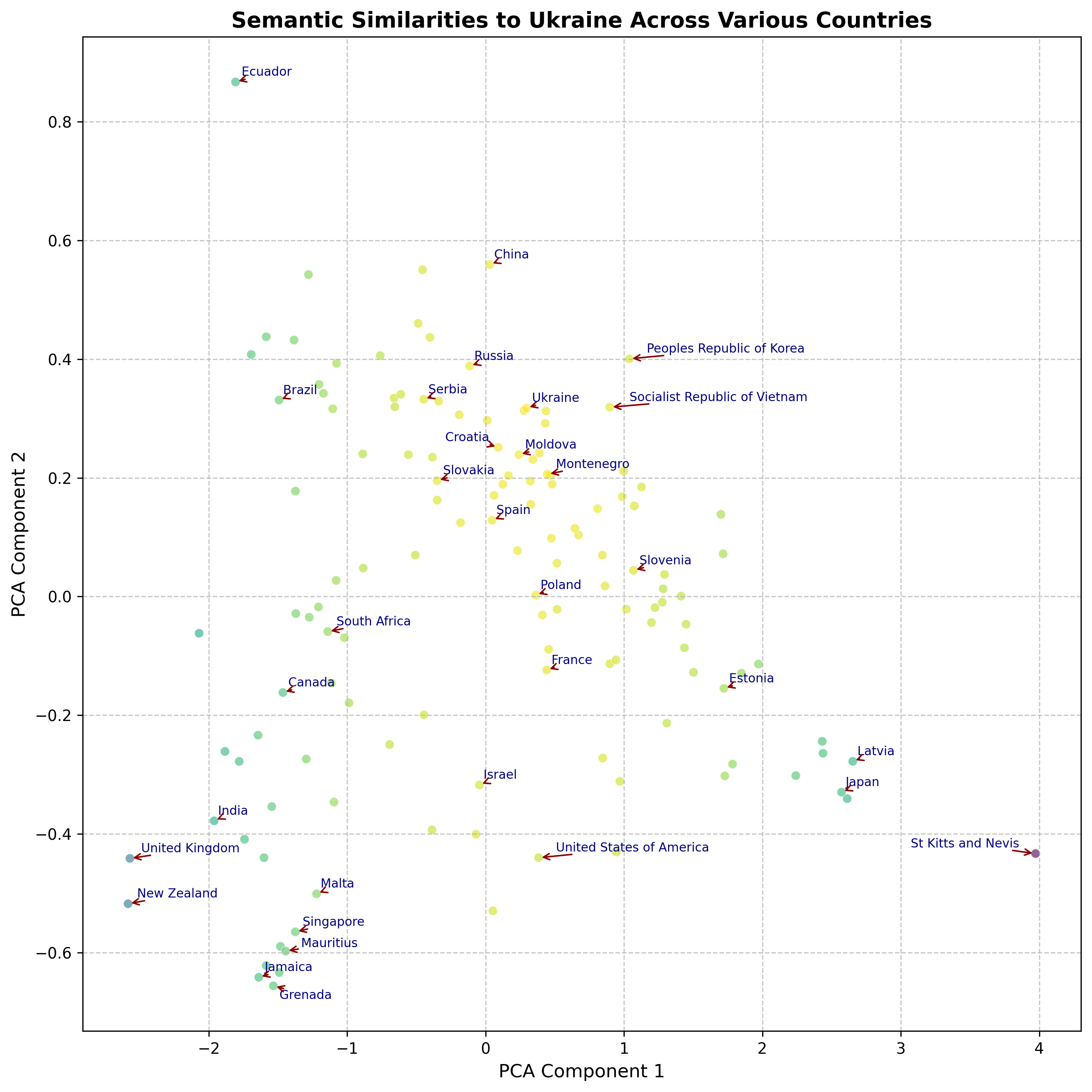

Given the prevailing desire and discussion in Ukrainian society to diverge from a similar authoritarian trajectory, the question arises: does the current semantic structure of the Ukrainian constitution align with this objective? To answer this question we employ a modern transformer-based language model to analyze 135 active global constitutions. This corpus, comprising 2,709,569 words, is not just a collection of legal texts but a reflection of diverse cultural, geographical, and historical narratives. The sheer diversity within this dataset offers a unique opportunity to understand how different nations conceive the tenets of governance and liberty.

Method

In the constantly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI), one of the most groundbreaking developments has been the advent of Language Models, particularly those based on transformer technology. These models are revolutionizing the way we analyze and interpret large sets of text data, offering insights and understandings that were previously unattainable.

The concept of embeddings is central to understanding how these models work. Imagine each word or phrase from a document being converted into a series of numerical values or vectors. This process is akin to creating a unique fingerprint for each word, capturing its essence and contextual meaning.

To illustrate embeddings in a more relatable context, imagine a simple sentence: "The cat sat on the mat." In this sentence, each word is transformed into an embedding. The model recognizes not just the individual words, but also their relationships and positions – the fact that the "cat" is the subject doing the sitting, and the "mat" is the object being sat upon.

More technical details

We use the Longformer model, and for each constitution, we break it into smaller parts of around 4000 words each to manage the model's token limit constraints. Along with these text snippets, we also pass the Title, Article names, and human-written markings for each section, to help the model maintain the general context.

For each snippet, we employ a mean-pooling technique to grasp more general information from the text. This technique averages the embeddings of words in a snippet, providing a generalized representation. We then aggregate the embeddings for all text snippets to produce the general vector space for the given constitution. This approach results in a multidimensional vector of embeddings that capture the semantic structure of the document.

To meaningfully analyze this and to extract only the high-level features of the text, we use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of dimensions to 2, facilitating easier visualization and comparison while retaining key variations in the data.

This approach allowed us to extract the high-level structure of 135 constitutions and meaningfully plot them on a 2D scale in a matter of minutes – a task that would take multiple years for human experts to replicate.

Results

Our analysis reveals that:

1) The Ukrainian constitution occupies a central position on the 2D scale, closely aligned with other Central and Southern Slavic nations. This finding aligns with expectations considering the shared historical and cultural contexts of these regions. The proximity of the Ukrainian constitution to its Slavic counterparts highlights the deep-seated cultural and historical ties that influence constitutional frameworks.

2) An expected revelation from our study is the structural and semantic resemblance of the Ukrainian constitution to the Russian constitution. It is also important to note that this finding is not universal among post-Soviet states. For instance, the constitutions of Latvia and Estonia are semantically closer to Westernized countries like the United States, France, and Japan, indicating a significant shift in their constitutional ethos away from their Soviet past. On the other hand, the Ukrainian constitution is spatially closer to the Russian constitution, raising significant discussion about the country's overall direction toward democratization.

3) An intriguing aspect of our analysis is the role of PCA component 2 (y-axis) in delineating a liberal-authoritarian divide among nations. Countries typically considered more liberal are found towards the bottom of the scale, while those with authoritarian leanings appear closer to the top. The majority of nations are scattered in the middle, reflecting a spectrum of governance models.

Our research went a step further to validate this observation by correlating our findings with the Democracy Index. The results showed a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.40 at high significance, indicating a meaningful relationship between PCA component 2 and the Democracy Index. Additionally, other metrics from the "Constitute Project," such as the level of judicial independence and the number of liberties codified in constitutions, were analyzed. Remarkably, PCA component 2 emerged as the best single predictor of a nation's democratic status.

In this context, the Ukrainian constitution notably ranks lower, positioned in the upper part of the graph, indicative of a more authoritarian orientation. This places it closer to countries like Russia and China, both of which occupy similar positions on the scale.

Conclusion

“Burn out in yourself even the traces of Russian subculture. Burn away all the memories from your childhood that are connected with anything Russian and Soviet...” — Roman Ratushnyi, Kyiv Activist

Our semantic analysis of global constitutions, with a focus on Ukraine's alignment, presents a compelling narrative. Despite Ukraine's efforts to distinguish itself from Russia and align with democratic movements in the West, our study reveals that its constitution bears a closer resemblance to Russia’s than to those of Western democracies like Poland, the UK, the USA, and France. This finding is pivotal, not as a point of criticism, but as an opportunity for introspection and progression.

As Ukraine continues to navigate its complex geopolitical landscape, this revelation should serve as a catalyst for a thorough review of its constitution. The goal here is not to undermine the current document but to invigorate a national conversation about how it can evolve to more accurately reflect the democratic aspirations and values of the Ukrainian people. It's a call for the nation to reassess and potentially recalibrate its constitutional compass.

This is a moment for legal scholars, political leaders, and citizens alike to engage in a constructive dialogue about their constitution. It's an invitation to consider how this fundamental document might be amended or reinterpreted to more closely align with the democratic ethos that Ukraine strives to embody. Such a process of review and revision is not just a legal exercise; it's a reaffirmation of a nation's identity and a declaration of its aspirations.

Ultimately, the path to a more representative and democratic constitution is a journey that demands courage, introspection, and collective effort. It's an opportunity for Ukraine to script a constitutional narrative that not only reflects its present-day realities but also paves the way for a future anchored in democratic ideals and practices.